Zinovy’s musings on the history of religions.

Zinovy’s musings on the history of religions.

The three so-called “western” religions were the most disruptive, so they had been the focus of the Regime’s purge. An image—red-splattered—flashed across the back of Zinovy’s mind and his stomach turned over.

Islam had been the first to go. In most of the world before the new regime came to power, Islam was a civilized belief system. Modern Muslims interpreted their prophet’s call to jihad symbolically, practicing jihad on the evil in their own hearts, warring against the infidel within. But in some parts of the world extreme fundamentalism prevailed.

This form of jihad had terrorized the developed nations for years until, finally, the new regime brought it down. The purge left virtually no societies intact over a wide swath of geography through the equatorial regions of the Middle East. Only a few Bedouin groups survived. Primitive, nomadic, and steeped in pre-Islamic superstitions, they posed no threat to anyone.

Christianity had gone next. By the time the new government was in place, the Christian world had “evangelized” the globe, claiming over half the world’s population, including most of Zinovy’s motherland. But Christian belief was harshly divided in the end, polarized by two radical extremes.

The conservative element were hard-liners, unwilling to compromise on anything. Their inflexibility had been their undoing. Intolerance could no longer be tolerated by the shapers of the sophisticated societal structure that was so necessary for the survival of all human beings in an increasingly crowded global community. Conservative Christianity had disintegrated, losing many of its adherents to political pressure and even more, strangely, to the natural disasters that had mushroomed during the years just before the establishment of the new regime. The more liberal element of the faith had been no problem. They were less dogmatic, and so had blended easily into the universal program.

Much to Zinovy’s surprise, Judaism, in some ways the least attractive of them all, had survived the longest. From the first, the new government had seemed unusually conciliatory to the worst of the lot—a tiny remnant of conservative Jewish holy men who were determined to reinstate the old fundamentalist form of the Jewish religion. With the Regime’s permission, these eccentrics began performing a bizarre act of worship that had not been practiced by any religion in over two thousand years.

And this was Zinovy’s troubling, bloody memory.

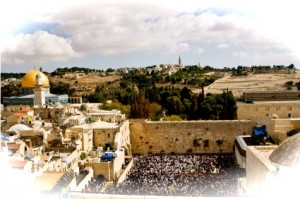

It was a primitive, senseless ritual, but within days of the Regime’s takeover, these conservative priests had set up altars on the plaza before the new Jewish temple that had replaced the Muslim Dome of the Rock in the center of Jerusalem. Zinovy had been there at the time, as a tourist. He’d watched the first of the violent animal sacrifices that began that day and continued, one after another, day after bloody day.

Zinovy was not sorry religion had disappeared. He was not into blood-stained opiates.